Indian Policy in Early Pennsylvania Can Be Best Described as

Relations betwixt Pennsylvania'south Native American and European peoples underwent cataclysmic change during the second half of the eighteenth century. Despite the reputation for peaceful intercultural relations that Pennsylvania had enjoyed since its founding in 1681, a series of wars engulfed its frontiers after 1754, leading to the dispossession and exile of the colony's native peoples. During the 7 Years' War, which lasted in North America from 1754 to 1760, the colony that William Penn had envisioned as a "peaceable kingdom" became instead the scene of some of the virtually horrific interracial violence in early America. The disruption of Pennsylvania's Indian relations acquired a deep political rift to open between Philadelphia's Quaker customs and colonists living along the Susquehanna Valley frontier. By the 1790s, Native Americans and Pennsylvania'due south European peoples were permanently estranged from each other, and no Indian nations retained secure possession of homelands within the state'due south borders.

By 1754, European colonization had substantially altered the location and number of Native Americans in Pennsylvania. The Delawares (besides known as Lenapes) had been mostly dispossessed from the river valley that was their original homeland. Despite being stripped of their claim to the Lehigh Valley by the Walking Buy (1737), some Delawares still lived in that region in Moravian missions while others remained in small towns in central and southern New Jersey. Many Delawares had migrated into the Susquehanna Valley and the Ohio-Allegheny region, which was called the "Ohio country" by colonists. Elsewhere, Indians from the northern Chesapeake Bay and North Carolina migrated into the Susquehanna Valley in the early eighteenth century. By the 1740s, two Indian towns with polyglot populations had get important centers in Pennsylvania's Indian relations: Conestoga in Lancaster County and Shamokin, at the juncture of the north and due west branches of the Susquehanna (modern Sunbury). Further west, Delawares who settled in the Ohio country were joined in that location by Shawnees and Senecas who were also drawn to the region past its bountiful resources. Thus, on the eve of the Seven Years' War, Pennsylvania's native population included a number of groups that had already experienced the consequences of colonization. By moving into the Susquehanna and Ohio regions, where they amalgamated with each other, these groups established new homelands and new alliances to defend them.

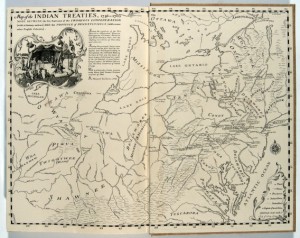

The Iroquois league fabricated several land deals with Pennsylvania, ceding the land of other tribes without their consent. This map shows the country deals made betwixt Pennsylvania and the Iroquois from 1736 to 1792. (Historical Social club of Pennsylvania)

In 1754, the Natives' merits to these homelands came under attack from several directions. Agents interim on behalf of the Penn family unit and Connecticut's Susquehannah Company completed country purchases with the Iroquois Indians of New York who ceded significant portions of western Pennsylvania without any approval from the Indians who lived at that place. Virginian land speculators raced against the Penn family to lay claim to the Ohio land, once again relying on cooperative Iroquois from New York. At the same time, the French asserted their possession of the region by edifice forts between Lake Erie and the Ohio River. After a British army commanded past General Edward Braddock was defeated by a French and Indian forcefulness at the Monongahela River in July 1755, state of war engulfed the Pennsylvania frontier. Delawares and Shawnees supplied past the French at Fort Duquesne (modern Pittsburgh) raided borderland communities in a wide arc from northwestern New Jersey through the Lehigh Valley to the Juniata River, taking captives, destroying livestock, and killing poorly dedicated settlers. Pennsylvania'southward government responded by instituting scalp bounties that encouraged indiscriminate reprisals against any Indians within the colony's borders.

Easton Treaty of 1758

A Delaware Indian named Teedyuscung (1700?-1763) emerged as an important intercultural diplomat at a serial of treaty conferences convened in Easton, Pennsylvania, between 1755 and 1758. Teedyuscung claimed to represent ten Indian nations, only his chief objective was securing the Delawares' possession of the Wyoming Valley, along the northern branch of the Susquehanna River (most modern Wilkes-Barre). In negotiations with the Pennsylvanians and other British colonial officials, he asserted the Pennsylvania Indians' independence from the Iroquois. In this try, he was supported by Philadelphia Quakers who sought to restore peace past exposing the fraudulent land purchases William Penn'south heirs had made with the Iroquois. Although neither Teedyuscung nor the Quakers succeeded entirely in their mission, the Easton Treaty of 1758 did finish Pennsylvania'south Indian war by restoring some of the disputed territory and by promising that the British would evacuate the Ohio country subsequently the French had been defeated.

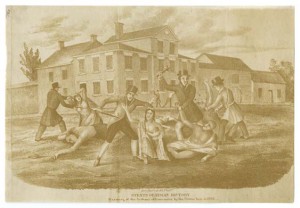

The Paxton Boys were a vigilante group that led a violent raid on the Conestoga tribe'south small settlement in December 1763. All members of the tribe were killed. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

An uneasy peace returned to Pennsylvania after 1758, simply the state of war had permanently contradistinct relations there betwixt native and European peoples. Pennsylvania colonists, despite their indigenous and cultural differences, came to see themselves equally sharing a mutual, racially-defined "white" identity in dissimilarity to the Indians' "savage" one. In the Ohio land, a Delaware prophet named Neolin (fl. 1760) preached a doctrine of "separate paths," urging Indians to revive ancient community and spurn Christianity, alcohol, and other aspects of colonial civilization he held responsible for corrupting the native fashion of life. This revivalist bulletin fueled a pan-Indian resistance to the soldiers and settlers who began moving into the Ohio and Susquehanna regions after 1758. In 1763, renewed hostilities sparked by military occupation and land-grabbing bankrupt out in western Pennsylvania. Pontiac's War (1763-65) plunged the Pennsylvania borderland into another moving ridge of violence, including an Indian siege at Fort Pitt (the British post built on the site of the onetime Fort Duquesne), during which British officers discussed using smallpox equally a biological weapon confronting the enemy. In Lancaster County, a group of colonial vigilantes known as the Paxton Boys murdered the Native population of Conestoga Indian Town, which had been allied with the Pennsylvania authorities since 1701. The Paxton Boys then marched on Philadelphia, threatening to kill Indians from the Moravian missions who had sought refuge there, only intervention by Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) and other city leaders prevented further violence.

By 1765, a decade of warfare had altered the power dynamic in Pennsylvania's Indian relations. Quakers no longer exerted moral or political dominance in the colony'south Indian policy. Instead, borderland settlers assumed all Indians were hostile and tacitly condoned their exile or murder. Speculators from within and exterior the colony competed confronting each other for Indian land, paying niggling heed to the retrocessions that natives had negotiated at Easton in 1758. At the Fort Stanwix Treaty of 1768, the British Crown'southward Indian agent Sir William Johnson (1715-74) conducted all the same some other land sale with the Iroquois that ceded Delaware and Shawnee homelands without their consent.

The Revolution's Toll on Indians

Seneca war chief Cornplanter fought in the Seven Years' State of war and Revolutionary State of war and helped negotiate the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. He was given a tract of land by the U.Due south. authorities that became the last Native American enclave in Pennsylvania. (Wellcome Images)

The American Revolution accelerated Indian dispossession in Pennsylvania. Freed from the restraints of British majestic authority, the Americans attacked and uprooted Native populations. A Continental Regular army expedition in 1779 laid waste to Indian towns in the northern Susquehanna and Allegheny Valleys. In March 1782, militiamen from the Pittsburgh area murdered nearly 100 Delaware men, women, and children in the Moravian mission town of Gnadenhütten in the Ohio country. By the war'due south end, nearly every Indian customs inside Pennsylvania's borders had either been destroyed or abandoned and their survivors forced to seek refuge in Ohio or New York. The state of Pennsylvania recognized no federal or land Indian reservations within its borders. By the 1790s, simply 1 small Indian customs remained within Pennsylvania: a group of Seneca Indians who lived forth the Allegheny River on state privately endemic by their leader, Cornplanter (c. 1750-1836). Cornplanter'due south Town remained on this belongings until its inhabitants were forced to relocate onto Seneca reservation lands in New York by the construction of the Kinzua Dam in the 1960s.

Despite the fact that Indians and colonists alike oftentimes invoked the retentiveness of William Penn in their treaty negotiations, the Quaker founder's vision of a peaceable kingdom in Pennsylvania never came to fruition. The Penn family's hunger for Indian land contributed to this deterioration in relations, but other causes included the militarization of Pennsylvania's frontier later on 1754, the unstoppable stream of settlers who invaded Indian territory, and the intrusion of imperial officials and country speculators from other colonies into Pennsylvania's Indian affairs. About importantly, after 1754 the mosaic of ethnic identities within Pennsylvania hardened into two split and diametrically opposed racial categories: white and Indian. Europeans pursued policies that denied natives membership in the Pennsylvania republic, while natives trying to survive the onslaught of colonization decided that their best option was to motion beyond the accomplish of their European neighbors.

Timothy J. Shannon is Professor of History at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. His publications include Indians and Colonists at the Crossroad of Empire: The Albany Congress of 1754 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000) and Iroquois Affairs on the Early American Frontier (New York: Viking Penguin, 2008).

Copyright 2015, Rutgers Academy.

Dowd, Gregory Evans. War under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, and the British Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Academy Press, 2002.

Jennings, Francis. Empire of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies, and Tribes in the 7 Years War in America. New York: W.Westward. Norton, 1988.

Kenny, Kevin. Peaceable Kingdom Lost: The Paxton Boys and the Destruction of William Penn'southward Holy Experiment. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Merrell, James H. Into the American Forest: Negotiators on the Colonial Pennsylvania Frontier. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999.

Merritt, Jane T. At the Crossroads: Indians and Empires on a Mid-Atlantic Borderland, 1700-1763. Chapel Hill: Academy of North Carolina Printing, 2003.

Preston, David L. The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667-1783. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009).

Richter, Daniel K. Native Americans' Pennsylvania. University Park: Pennsylvania Historical Association, 2005.

Schutt, Amy C. Peoples of the River Valleys: The Odyssey of the Delaware Indians. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Printing, 2007.

Shannon, Timothy J. Iroquois Diplomacy on the Early American Frontier. New York: Viking Penguin, 2008.

Silver, Peter. Our Barbarous Neighbors: How Indian State of war Transformed Early America. New York: W.W. Norton, 2007.

Wallace, Anthony F. C. Rex of the Delawares: Teedyuscung, 1700-1763. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1990.

Ward, Matthew. Breaking the Backcountry: The 7 Years' War in Virginia and Pennsylvania, 1754-1765. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004.

Additional Reading

Boyd, Julian P., ed.Indian Treaties Printed by Benjamin Franklin, 1736-1762. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1938.

Jennings, Francis, et al., eds.The History and Culture of Iroquois Diplomacy: An Interdisciplinary Guide to the Treaties of the Six Nations and Their League. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1985.

Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, sixteen volumes. Harrisburg: 1852-53.

Source: https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/native-american-pennsylvania-relations-1754-89-2/

0 Response to "Indian Policy in Early Pennsylvania Can Be Best Described as"

Postar um comentário